A problem statement is a concise and clear description of an issue or challenge that needs attention. It’s important to write a good problem statement because it helps define the problem, guide research efforts, and communicate its importance. Whenever we run almost any kind of workshop here at Now Go Create, we spend time helping our clients to get to a useful, interesting starting point. If you’re familiar with the idea of a design sprint, then you’ll know that this is the first stage to that process too.

Here are some key points to consider when crafting a problem statement:

1. Be clear and specific: Make sure your problem statement clearly states the problem in a specific and straightforward way. Avoid using vague language and provide enough details for everyone to understand what you’re talking about.

2. Give context: Provide background information to help others understand why the problem matters. Explain the current situation, any gaps or challenges, and the potential consequences if the problem isn’t addressed.

3. Set measurable objectives: Clearly define what you want to achieve by solving the problem. Make sure these objectives are measurable and realistic, so you can evaluate progress effectively.

4. Think about stakeholders: Consider the perspectives and needs of the people affected by or interested in the problem. Understanding their viewpoints will help you frame the problem statement and identify potential solutions.

5. Make it researchable and actionable: Ensure that it’s possible to gather information and data to analyze and propose solutions. Your problem statement should provide a clear direction for taking action.

6. Highlight impact and benefits: Clearly explain the positive outcomes that solving the problem can bring to individuals, organizations, or society as a whole. Showing the significance of resolving the issue will generate support and resources for finding solutions.

Writing a good problem statement is crucial because it lays the foundation for effective problem-solving. It helps everyone focus their efforts, guides research, and provides a framework for evaluating potential solutions. A well-crafted problem statement ensures that everyone understands the problem’s scope and importance, increasing the chances of finding meaningful and sustainable solutions.

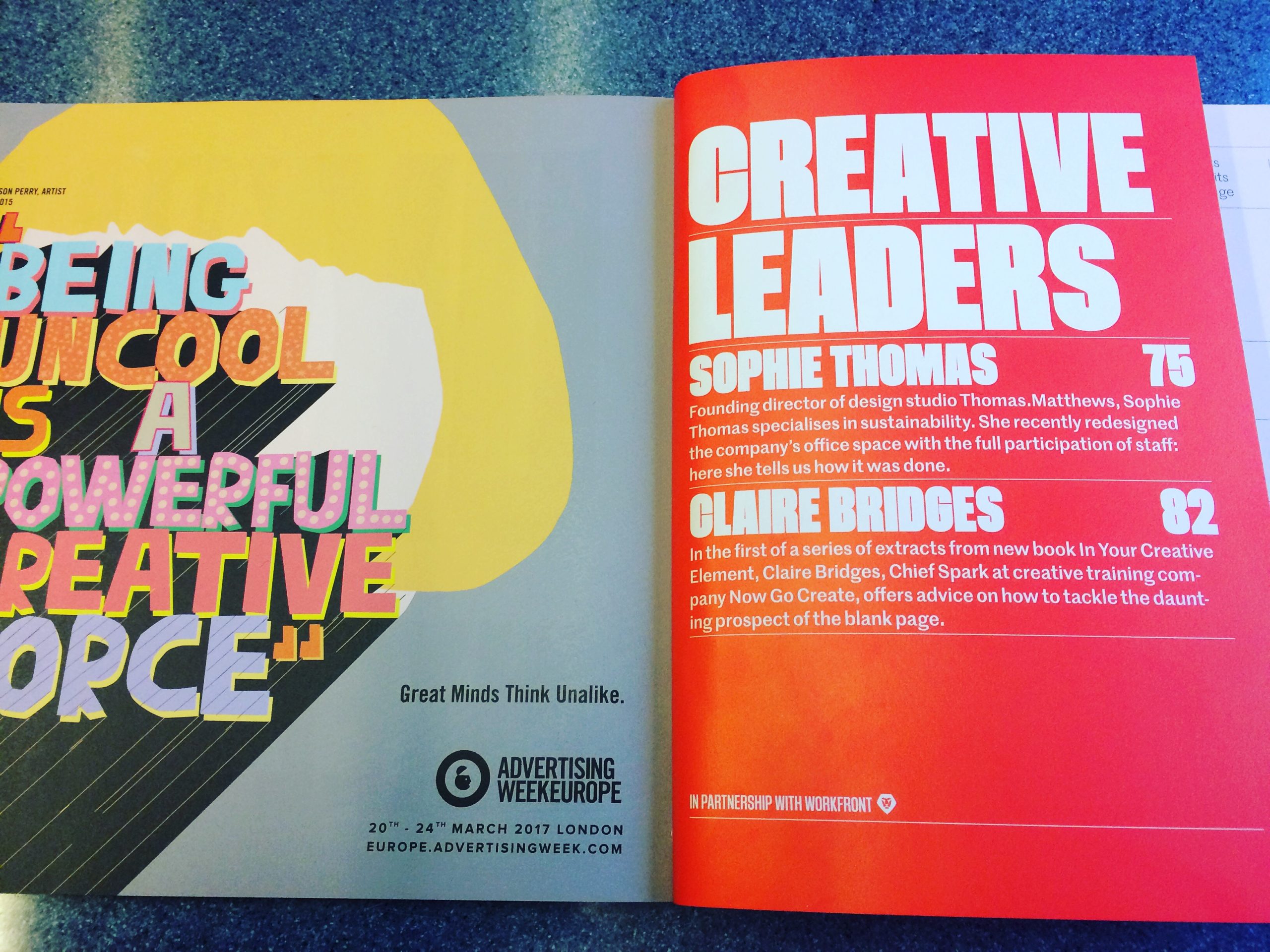

I thought I’d share some of the tips on writing a great problem statement from my book In Your Creative Element, where I suggest on how to identify the problem at hand and that can be applied to a diverse range of problems – from ‘I need an idea right now’ to more complex challenges.

Problem finding tool 1:

Generating an effective problem statement (Isaksen et al, 2011)

What is it? A tool from the Creative Problem Solving process to generate useful problem statements and open up ideas. Often a challenge is not written as a question, but as a statement or an objective. For example: stunt ideas to support our World Cup sponsorship or get more ‘likes’ on Facebook. You need to bridge between the client brief and an enticing creative brief. This tool helps to do that and can add specificity, constraints and ambition to your statement.

How to do it: Follow this format to create potential problem statements, informed by data and insight.

Write down your initial problem as you see it, or as per the client brief. Here’s a working example of a challenge that I see every time I take a commuter train. People often fall asleep on the train without having their ticket on display for the guard. How can we make people leave their ticket out?

1. Start with an invitational stem – a way of asking questions that ‘opens up, or invites, many possible responses’. There are three suggested stems:How to…

How might…

In what ways might…

2. Identify an owner. This might be a specific person responsible for the problem or a company eg How might Loco Trains’ corporate communications team….In what ways might Loco Trains’ staff…. In what ways might Loco Trains’ guards…. How to encourage commuters to….

By playing with the ownership you give yourself options. You can change the gender, the demographic, the age, to give you different (divergent) avenues.

3. Have an action verb. “Identify a specific and positive course envisioned by the statement” (Isaksen et al, 2011); eg “In what ways might Loco Trains’ guards force/ encourage/ cajole/ provoke/ avoid/ reward/ persuade….

4. An objective. “Identify the target or desired outcome and direction for your problem-solving activity” (Isaksen et al, 2011).

So:

- In what ways might the Loco Trains’ guard reward customers for showing their tickets?

- How to avoid awkward customer interactions on the train?

- How might the Loco Trains design team create a ticket holder that people actually want to show off?

- How to engage with Claire on the 6:05am London Waterloo train and encourage her to display her ticket without being prompted?

Again, changing the owner, the verb and the outcome (being specific and general) gives you different creative options and opens up different routes.

You can ask yourself whether, from all the options you generate, is there a ‘central question’? One that takes priority over all the others and that gives you a clear way into your problem?

Who is this technique for? Anyone involved at the start of the creative process.

Good for: Ensuring that you’re asking the right question. Checking that you have a well-formed problem if you’re having difficulty generating ideas (often due to a poor question).

Not so good for: There’s really no occasion when having a well-formed question will hinder your creative efforts!

This is an extract from my book In Your Creative Element with a full toolkit of 25 tried and tested tools click here.